"SKINNER IS ASKING THE HIGH COURT TO ADDRESS A PROCEDURAL QUESTION ON WHICH COURTS ACROSS THE COUNTRY HAVE SPLIT: WHETHER HE SHOULD BE ALLOWED TO PRESS A FEDERAL CIVIL RIGHTS LAWSUIT SEEKING TO HAVE ADDITIONAL DNA EVIDENCE IN HIS CASE TESTED INSTEAD OF PURSUING A WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS. THE ANSWER TO WHAT MIGHT SEEM TO BE A SIMPLE PROCEDURAL QUESTION COULD HAVE FAR-REACHING IMPLICATIONS FOR OTHERS LIKE SKINNER WHO CLAIM INNOCENCE AFTER THEY'VE BEEN CONVICTED. A HABEAS CORPUS CLAIM REQUIRES A DEFENDANT TO PROVE HE WAS WRONGLY IMPRISONED. SKINNER'S ARGUMENT IS DIFFERENT: HE'S ASSERTING A CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT TO PROVE HE'S INNOCENT DESPITE A JURY'S DECISION OTHERWISE IN A TRIAL CONDUCTED WITHOUT LEGAL ERROR. THE SUPREME COURT HAS FOR YEARS AVOIDED RULING THAT SUCH A RIGHT EXISTS, AND IT WON'T TAKE UP THAT CORE QUESTION NOW. A DECISION IN SKINNER'S FAVOR, RATHER, WOULD MERELY ALLOW HIM TO RAISE THAT QUESTION IN LOWER COURTS UNDER A CIVIL RIGHTS CLAIM. “WHAT’S BEING OBSCURED IS THE BIGGER DISCUSSION ABOUT WHETHER KNOWING THE TRUTH IS A RIGHT THAT PEOPLE REALLY OUGHT TO HAVE,” SAID JEFF BLACKBURN, THE GENERAL COUNSEL FOR THE TEXAS INNOCENCE PROJECT. "DNA HAS OPENED SORT OF A SCIENTIFIC DOOR FOR A COMPLETE RE-EXAMINATION OF THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM."

REPORTER BRANDI GRISSOM: THE TEXAS TRIBUNE;

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

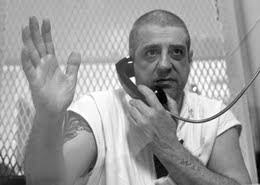

BACKGROUND: The editor of the Texas Tribune says in a note that "Hank Skinner is set to be executed for a 1993 murder he's always maintained he didn't commit. He wants the state to test whether his DNA matches evidence found at the crime scene, but prosecutors say the time to contest his conviction has come and gone......We told the story of the murders and his conviction and sentencing in the first part of this story." Reporter Brandi Grissom, author of the Tribune series on Hank Skinner, writes: "I interviewed Henry "Hank" Watkins Skinner, 47, at the Polunsky Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice — death row — on January 20, 2010. Skinner was convicted in 1995 of murdering his girlfriends and her two sons; the state has scheduled his execution for February 24. Skinner has always maintained that he's innocent and for 15 years has asked the state to release DNA evidence that he says will prove he was not the killer." Grissom has done a superb job of bringing the Skinner case to the attention of the public."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Death row inmate Hank Skinner bought himself some time Monday when the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to take up a technical issue in his case, but legal experts say he's unlikely to escape his ultimate punishment," the Texas Tribune story by reporter Brandi Grissom, published earlier today under the heading, "Justice Delayed," begins.

"Skinner is asking the High Court to address a procedural question on which courts across the country have split: whether he should be allowed to press a federal civil rights lawsuit seeking to have additional DNA evidence in his case tested instead of pursuing a writ of habeas corpus," the story continues.

"The answer to what might seem to be a simple procedural question could have far-reaching implications for others like Skinner who claim innocence after they've been convicted. A habeas corpus claim requires a defendant to prove he was wrongly imprisoned. Skinner's argument is different: He's asserting a constitutional right to prove he's innocent despite a jury's decision otherwise in a trial conducted without legal error.

The Supreme Court has for years avoided ruling that such a right exists, and it won't take up that core question now. A decision in Skinner's favor, rather, would merely allow him to raise that question in lower courts under a civil rights claim.

“What’s being obscured is the bigger discussion about whether knowing the truth is a right that people really ought to have,” said Jeff Blackburn, the general counsel for the Texas Innocence Project. "DNA has opened sort of a scientific door for a complete re-examination of the criminal justice system."

Skinner argues that DNA evidence that police gathered at the scene of the 1993 triple murder — a knife, a rape kit, a man’s windbreaker and other biological material — could show he is innocent. The material was never tested because other DNA evidence that was tested had helped to implicate Skinner, and his original trial attorney did not want to take the chance that more testing would do the same. An earlier appeal of Skinner's based on claims his original lawyer was ineffective failed. And Texas courts have denied Skinner's requests under habeas corpus laws to test the evidence. But in March — about an hour before he was set to walk into the death chamber — the Supreme Court issued a stay, and now it will decide whether to allow him to proceed under federal civil rights law.

Skinner’s lawyers filed the civil rights lawsuit — alleging that his constitutional rights were violated by the state’s unwillingness to allow him access to the untested DNA evidence — as his options under habeas corpus were running out. The Fifth Circuit Court rejected his case. The court said Skinner’s pursuit of DNA evidence is aimed at getting his sentence overturned and so it must be a habeas case, not a civil rights case. Skinner’s lawyers argue that he should be allowed to bring the case under civil rights laws because the DNA testing wouldn’t necessarily lead to a reversal of his conviction. There’s no guarantee that he would be granted testing by the lower federal courts. Even if lower courts were to order testing — and the results showed he was innocent — that doesn’t mean automatically Skinner would be taken off death row, his attorneys argue.

Gray County District Attorney Lynn Switzer, who is named in the lawsuit and is the most recent prosecutor to deal with Skinner's case, released a statement Monday expressing frustration with the case, which has dragged on for more than 15 years. In the statement, published online by KVII in Amarillo, Switzer said that she remains in contact with the victims' family and friends, and they oppose allowing additional DNA testing. Skinner had a fair trial, she said, and the jury's decision should be respected. "If defendants are allowed to 'game the system' then we will never be able to rely on the finality of the judgments entered in their cases," Switzer said.

Habeas corpus claims typically are ones that could lead to a defendant's sentence being overturned after proving that he was wrongfully imprisoned. Civil rights claims, on the other hand, usually allow a defendant to prove his constitutional rights were violated in some way during or after trial and don't always seek to reverse his sentence. Five circuit courts allow defendants to bring DNA testing requests under federal civil rights law, but two circuit courts — including the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal, which has jurisdiction over Texas and Skinner's case — require such claims to be filed under habeas corpus laws.

“The courts are very resistant to habeas claims,” said Christopher Slobogin, a professor at Vanderbilt University Law School in Nashville. “To put it bluntly, they get tired of these claims.” The Supreme Court has ruled in the past that convicts seeking to have their sentences overturned must file habeas claims. But those cases are some of the hardest to win, because they have a much higher standard of proof.

"Not likely to win"

Though getting the Court to take up Skinner’s question was a win for him and his team of lawyers, legal experts said the victory — probably his last chance to get the DNA testing done before he is executed — might be fleeting. “In the end, Skinner’s not likely to win here,” said Joseph Hoffmann, a death penalty expert and law professor at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law.

Slobogin said he expected the High Court to rule against Skinner and decide that his DNA request cannot be a civil rights issue. “The Supreme Court has said that when attacking the validity of a sentence, habeas is the appropriate venue,” he said. If the court agrees with Skinner that inmates can request DNA testing under civil rights laws, he said, there could be a rush by others to file similar requests. “I think it’s fair to say there’ll be an increase in DNA-type challenges to convictions if the court holds” Skinner can seek testing under civil rights law, Slobogin said.

Even if the Court agreed that Skinner can request DNA testing under federal civil rights law, Hoffmann said it’s unlikely the courts would rule that he has a constitutional right to prove he was actually innocent. The Supreme Court has never ruled that the Constitution spells out such a right. It’s likely that Skinner’s case or a similar one would make its way back to the Supreme Court and eventually force the court to face that question. If the Court were to answer it affirmatively, Hoffmann said, it could start a flood of litigation from inmates claiming innocence. That, in turn, could raise a myriad questions about how the justice system operates and really “gum up the works,” he said. “They really don’t want to kind of bite the bullet and recognize this as a federal constitutional right.”

Allowing DNA requests under federal civil rights law would also bring the Supreme Court closer to a larger question that Blackburn and Hoffmann said the elite jurists have carefully avoided: whether inmates have a constitutional right to prove they are actually innocent. With the rise of DNA science, the question looms large in cases such as Skinner's, where testable evidence exists that the jury never heard. Currently, federal innocence claims are primarily based on deprivation of an inmates’ constitutional right to due process — things like shoddy representation or biased juries. There is no legal remedy for convicted criminals who claim the jury just got it wrong, even though their rights were properly protected at trial, Hoffmann said.

"Whether they’re actually innocent or not is kind of a legal irrelevancy once the jury has spoken its version of the truth,” Hoffmann said. “Basically, our legal system is constructed in such a way that that’s the end of it.”"

The story can be found at:

http://www.texastribune.org/stories/2010/may/25/legal-sideshow/#

Harold Levy...hlevy15@gmail.com;