.

"In April of our senior year, the four of us -- 22-year-old journalism students from Northwestern University's Medill Innocence Project -- arrived in Texas in search of the jurors. (The trial had been moved to the Fort Worth area from rural Gray County in the Panhandle because of massive pre-trial publicity.) The Medill Innocence Project investigates possible wrongful convictions in homicide cases. In the five days allotted for our reporting trip, we hoped to get in touch with at least one juror. We were pleasantly surprised, however, when more than half the jury opened their doors and memories."

MEDILL INNOCENCE PROJECT; Rachel Cicurel, Gaby Fleischman, Emily Glazer, and Alexandra Johnson. AOL: POLITICS ONLINE;

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

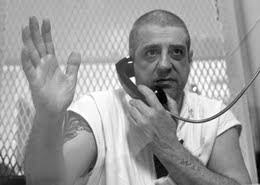

BACKGROUND: The editor of the Texas Tribune says in a note that "Hank Skinner is set to be executed for a 1993 murder he's always maintained he didn't commit. He wants the state to test whether his DNA matches evidence found at the crime scene, but prosecutors say the time to contest his conviction has come and gone......We told the story of the murders and his conviction and sentencing in the first part of this story." Reporter Brandi Grissom, author of the Tribune series on Hank Skinner, writes: "I interviewed Henry "Hank" Watkins Skinner, 47, at the Polunsky Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice — death row — on January 20, 2010. Skinner was convicted in 1995 of murdering his girlfriends and her two sons; the state has scheduled his execution for February 24. Skinner has always maintained that he's innocent and for 15 years has asked the state to release DNA evidence that he says will prove he was not the killer."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"In March 1995, a jury left a Fort Worth, Texas, courthouse having unanimously decided that DNA testing and compelling testimony led to an inescapable verdict: Henry "Hank" Skinner deserved to die for the murders of his live-in girlfriend, Twila Busby, and her two adult sons in their home on New Year's Eve 1993," the account, published on AOL's Daily Politics Blog begins, under the heading, "Hank Skinner Death Penalty Case: Texas Jurors Reconsider Verdict."

"Twila was bludgeoned to death; her sons were stabbed," the account continues.

"The jury primarily based its decision on evidence that showed the victims' blood on Skinner's clothes and the testimony of a neighbor. They deliberated for less than two hours, and Skinner has been on Texas' death row ever since.

But the jurors were never presented with complete DNA results of the physical evidence, nor could they have imagined that the prosecution's star witness would recant her testimony and that subsequent developments would strengthen the case that another man may have been responsible for the murders.

Last month, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would take Skinner's case and determine whether he can bring a civil rights action to seek DNA testing of the remaining evidence found at the scene. The untested evidence includes vaginal swabs, bloodied knives, fingernail clippings, hair clutched in the female victim's hand, and a blood-stained windbreaker strikingly similar to one worn by the alternative suspect.

In April of our senior year, the four of us -- 22-year-old journalism students from Northwestern University's Medill Innocence Project -- arrived in Texas in search of the jurors. (The trial had been moved to the Fort Worth area from rural Gray County in the Panhandle because of massive pre-trial publicity.) The Medill Innocence Project investigates possible wrongful convictions in homicide cases. In the five days allotted for our reporting trip, we hoped to get in touch with at least one juror. We were pleasantly surprised, however, when more than half the jury opened their doors and memories.

In light of new developments that have surfaced in the 15 years since Skinner's trial, several of the original jurors are no longer sure of his guilt. Five say they might have had reasonable doubt at the time of the trial if they had known then what they know now. Seven are calling for DNA testing of all the evidence so they can be certain they convicted the right man. An eighth juror we contacted declined to comment.

Some jurors had followed developments in the case, searching the Internet and Texas newspapers for Skinner's name; others avoided it, hoping never to revisit this traumatic experience. In kitchens, livings rooms, garages, and eateries across Fort Worth and suburban Arlington, the jurors recalled the experience of being sequestered -- how detached they felt watching "Forrest Gump" rather than the news of the day.

But plugged back in 15 years later, they considered statements by two of Twila's friends that the alternative suspect -- Twila's uncle, Robert Donnell, who died in 1997 -- allegedly raped her on two occasions and stalked her at a party the night of the murders, as well as those by neighbors who said they had seen him tearing the carpeting out of his truck the morning after the crime and repainting the vehicle within a week.

They also took into account a new medical report indicating the likelihood that Skinner was barely conscious from drinking a mixture of alcohol and codeine at the time of the crime, and sworn statements by the prosecution's star witness, Andrea Reed, who repudiated her testimony. In the original trial, Reed, Skinner's ex-girlfriend who lived nearby, had testified that when Skinner came to her trailer shortly after the murders, he made incriminating statements and demanded that she not call police. But in 1997, she recanted her testimony to a private investigator, claiming that law enforcement had intimidated her into falsely testifying. In 2000, she repeated that claim to another group of Medill Innocence Project students.

"I had no idea that she recanted her story, her testimony; that brings new light," said Tiffany Daniel, the youngest member of the jury. "That puts a lot of questions in my mind."

Sitting at her kitchen table, Daniel slowly reintroduced herself to an experience she had closed well over a decade ago. "We were responsible for sentencing," she said. "If we weren't presented with all the evidence that could potentially free a man or convict a man...if [he's put to death] and if this man didn't do that, that would be something I have to live with."

Many of the jurors interviewed were taken aback by the amount of untested evidence, stunned that even the blood on two of the murder weapons had not been analyzed. The seven jurors agreed that all the evidence should undergo DNA analysis. "That's the only way you can come to the right conclusion of if he's innocent or guilty," said Danny Stewart, the jury's foreman. "I would hate personally to put a man to death if he's innocent."

Lynn Switzer, the current District Attorney of Gray County who is being sued by Skinner in the case before the Supreme Court, has refused to test all the remaining evidence. "If defendants are allowed to 'game the system' then we will never be able to rely on the finality of the judgments entered in their cases," Switzer said in a statement following the Court's decision to take Skinner's case. "Mr. Skinner has been given plenty of opportunity to show that additional testing could prove his innocence, but he could not show that."

Texas courts have repeatedly denied Skinner's requests for DNA tests, ruling that he should have had the testing done at the time of the trial, a position Switzer supports.

Switzer was appointed DA by Texas Gov. Rick Perry after District Attorney Richard Roach was convicted of stealing and abusing methamphetamines. In January 2005, the FBI arrested Roach in the Gray County courthouse -- a place where he had both injected meth in front of an employee and made a career of prosecuting constituents for using the same drug. Roach had ousted the late John Mann, who served Gray County during Skinner's trial in 1995.

At his trial, Skinner was represented by Harold Comer, another former DA of Gray County. In that role, Comer had earlier prosecuted Skinner on charges of theft and assault. Although Comer resigned from office in 1992 before pleading guilty to criminal charges of embezzling cash confiscated in drug cases, he was later appointed by the judge to represent Skinner at his capital murder trial. To many jurors' current dismay, however, Comer didn't request DNA tests prior to trial, saying he did this to protect his client from potentially damaging results.

"All of it should have been tested," juror Stewart said. "All the DNA evidence should be tested. Period."

Some additional tests were done following Skinner's conviction. After being confronted on CourtTV in 2000, Mann had a change of heart. He ordered additional tests on head hairs clutched in Twila's hand, bloody gauze on the front sidewalk of her home, a cassette tape in the bedroom, and other items.

While some results put Skinner in the home -- where he indisputably was at the time of the crime -- the tests on one of the head hairs, the blood on the sidewalk, the cassette tape, and an unmatched fingerprint found on a plastic bag containing a bloodied knife all excluded Skinner. At that point, the District Attorney's office -- led by Richard Roach when he took over from Mann -- halted further testing and returned the evidence to a storage locker, where it sits today.

It was this most recent round of DNA tests that prompted five jurors to say they could have reached a different verdict if they had known at the time of the trial what they know today. The other two said they really didn't know if the tests would have changed their minds.

"It would have been reasonable doubt," Daniel said, wiping away tears. "Especially if we had all that evidence, and another person's fingerprints was on it, or if someone else's skin was underneath Twila Busby's fingernails. That's reasonable doubt that it could be somebody else."

Douglas Keene, a jury expert and president of Keene Trial Consulting in Austin, said it is "not at all common" for jurors to question their original verdict. "Over time, they become more cemented into that original view because they can't even tolerate the view that they might have made a mistake on something so serious," he said.

Keene emphasized that jurors might feel anxiety that they may have come to the wrong conclusion, regardless of whether it was their fault. "Even if they didn't have an opportunity to know the exculpating evidence, jurors could become distraught that a man's life might have been taken in error."

But in Skinner's case, information suppressed during the trial and developed over the last 15 years has caused five jurors to contemplate their guilty vote in light of the high stakes Keene described. With someone's life on the line, Keene said, jurors take the burden of their responsibility very seriously.

In worn-in jeans and a t-shirt, juror Jerry Williams perched on a stool in his garage. He wonders now if DNA results could put the case to rest.

"What's right is right and what's wrong is wrong," Williams said. "It should have been tested before...Somebody's life is at stake."

Meanwhile, Hank Skinner remains on Texas' death row, within 47 minutes of execution on March 24 until the Supreme Court issued a stay. He has maintained his innocence since the night in 1993 that Twila Busby and her sons were murdered, and hopes the high court will give him the right to prove it."

The account can be found at:

http://www.politicsdaily.com/2010/06/09/hank-skinner-death-penalty-case-texas-jurors-reconsider-verdict/

Harold Levy...hlevy15@gmail.com;