"Skinner came within 45 minutes of being strapped down for lethal injection before the Supreme Court stayed his execution to hear his case. The justices' decision could come at any time.

The oral arguments in Skinner v. Switzer traversed the legal landscape of habeas corpus reviews and federal civil rights laws, but bypassed the question most nonlawyers would have: Why not just test the evidence?

If Skinner's crime had occurred in Dallas, instead of 350 miles northwest, the testing probably would have been done by now."

REPORTER ROBERT BARNES: THE WASHINGTON POST;

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

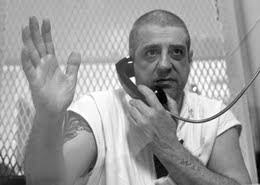

BACKGROUND: "Hank Skinner faces execution for a 1993 murder he's always maintained he didn't commit. He wants the state to test whether his DNA matches evidence found at the crime scene, but prosecutors say the time to contest his conviction has come and gone......We told the story of the murders and his conviction and sentencing in the first part of this story." Reporter Brandi Grissom, author of the Tribune series on Hank Skinner, writes: "I interviewed Henry "Hank" Watkins Skinner, 47, at the Polunsky Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice — death row — on January 20, 2010. Skinner was convicted in 1995 of murdering his girlfriends and her two sons; Skinner has always maintained that he's innocent and for 15 years has asked the state to release DNA evidence that he says will prove he was not the killer." Texas Tribune;

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"DALLAS - The news brings almost routine stories about wrongfully convicted prisoners who are exonerated by DNA testing, but they often have traveled widely divergent paths to freedom," the Washington Post story by reporter Robert Barnes published on February 14, 2011 under the heading, "Supreme Court confronts conflicting laws on post-conviction DNA testing," begins.

"In some states, only prisoners facing execution have the right to DNA testing to try to prove their innocence," the story continues.

"In others, anyone who pleaded guilty is barred from asking for the testing. In the patchwork of legislation passed by Congress and 48 states, even individual prosecutors can carry great weight.

The Supreme Court is again considering the tangled legal questions that accompany the issue in the case of Henry Skinner, who says DNA evidence could settle the question of whether he murdered his girlfriend and her two developmentally disabled adult sons.

Prosecutors in Gray County, Tex., where Skinner was convicted, are convinced that he is guilty and say he passed up a chance to test DNA evidence at his trial 15 years ago. Texas courts said he didn't meet the requirements of a state law that grants DNA testing to some convicts. Federal courts said they had no proper role in second-guessing Texas.

Skinner came within 45 minutes of being strapped down for lethal injection before the Supreme Court stayed his execution to hear his case. The justices' decision could come at any time.

The oral arguments in Skinner v. Switzer traversed the legal landscape of habeas corpus reviews and federal civil rights laws, but bypassed the question most nonlawyers would have: Why not just test the evidence?

If Skinner's crime had occurred in Dallas, instead of 350 miles northwest, the testing probably would have been done by now.

Dallas County District Attorney Craig Watkins, probably the country's most famous advocate of allowing access to DNA, set up a special unit for that purpose soon after taking office in 2007. Since then, 21 men convicted in Dallas have been exonerated by DNA testing.

"If there's DNA and the person is claiming his innocence, and you look at the case and there may be a possibility of it, what's the harm?" Watkins asked during a recent interview.

"If he's guilty, then the system worked. If he's not, then it didn't work, so let's fix it. I don't see the rationale in blocking a test where there's a legitimate question of innocence."

But those questions are a matter of deep disagreement. Those opposed to wide access to testing point to the expense for budget-strapped states and the potential for an unending cycle of legal maneuvering.

"If defendants are allowed to 'game the system,' then we will never be able to rely on the finality of the judgments entered in their cases," Lynn Switzer, the Gray County district attorney, said in a statement.

A divided Supreme Court decided in 2009 largely to leave the decision about testing up to Congress and the state legislatures, and their laws can vary widely.

When the majority declined to find that the convicted have a constitutional right to testing, it left a slim opening for those trying to prove that a state's procedures were inadequate.

Skinner's attorneys are trying to convince the court that the state court decisions in his case were so arbitrary that they violated his federal civil rights.

The court's ruling two years ago acknowledged that the technology is relatively new and said it is appropriate for states to experiment with their policies, even if that results in conflicting laws.

"The dilemma is how to harness DNA's power to prove innocence without unnecessarily overthrowing the established system of criminal justice," Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote.

'It's about justice'

Among the 21 men exonerated by DNA in Dallas is James Woodard, who spent 27 years behind bars for a murder he did not commit.

Woodard, who always maintained his innocence, was convicted in the 1981 killing of his girlfriend, Beverly Ann Jones, who also had been raped. "I stayed awake a lot of nights trying to [decide how] to present my case, because it was an innocence case," he said in a recent interview. "But you know, the law doesn't work that way. Justice and the law, they don't always run on parallel tracks."

After Texas passed its DNA access law in 2001, Woodard stepped up his efforts. DNA evidence from the rape had been preserved but never tested, because Woodard had not been charged with that crime. When it was tested, it showed that the semen was from another man.

"I wouldn't waste my time being mad at the system; I just got caught up in the mechanism of the law," Woodard said.

When Woodard was released in 2008, he became the longest-serving prisoner to be cleared by DNA - until last month, when Cornelius Dupree Jr. was freed after 30 years in prison for rape and kidnapping convictions.

Dupree was also among the 21 men exonerated by DNA testing since Watkins became district attorney; it is the most of any jurisdiction in the country.

Watkins, the first Democrat to be elected to the job in years and the first African American, found a backlog of 500 requests for DNA testing and a huge catalog of DNA evidence stretching back decades.

The unit he set up investigates the requests. But more important, he said, his prosecutors have begun to believe that part of their job is to aid those claiming innocence.

"When we free a person who didn't commit a crime, that's the work of a prosecutor," Watkins said. "A prosecutor's job is not just about convictions; it's about justice."

Watkins's initiatives have brought him national exposure but not a lot of friends among his fellow prosecutors. One particularly sharp critic is John Bradley, the district attorney in Williamson County, near Austin.

Bradley accused Watkins of securing a place on "the national stage" by implying that he is "the only prosecutor in Texas or anywhere else who is doing this."

The emphasis on exonerations obscures how few there are in a place such as Texas, Bradley said, where as many as 1 million people are convicted of crimes each year.

"What I object to is taking a few incidents and using them to try to make it seem like the justice system is broken," he said.

Bradley said the Texas law allows for DNA testing when it is appropriate. But many requests for testing, he said, are just the guilty "playing DNA lottery" and hoping for an outcome that might cast doubt on their convictions.

A Catch-22

With the issue now before the Supreme Court, some prisoner advocates say privately that they would have wished for a better test case than Skinner's.

He has maintained his innocence, despite acknowledging that he was present during the 1993 New Year's Eve slayings of his girlfriend Twila Busby and her two mentally disabled adult sons at the house they shared in the small Panhandle town of Pampa. Police found Skinner blocks away, hiding in the closet of a former girlfriend, in bloody clothes and with a gash in his hand.

He said that during the killings he was passed out on what tests showed to be a near-lethal combination of codeine and alcohol. He said he could not have overpowered and killed the three in his condition.

He said that he woke to find them dead and that the blood on his clothes came from examining them.

Prosecutors did not test all of the evidence from the crime scene, including material from a rape kit, hair, and skin cells under Busby's fingernails.

Strategic decisions seemed to be in play on both sides: Prosecutors did not need the extra evidence, and Skinner's attorney feared that more testing would only solidify the case against his client.

Skinner and his supporters, including Northwestern University's Medill Innocence Project, have pointed to Busby's now-deceased uncle, of whom she was afraid, as the possible killer. Skinner says that he always wanted the evidence tested.

Skinner's argument before the Supreme Court in October required some legal maneuvering. Court precedent would seem to indicate that he can use federal civil rights laws to get the evidence only if that evidence would not necessarily imply the wrongfulness of his conviction.

Skinner's attorney Robert Owen said that was the case because, in fact, there is a chance the evidence would prove him guilty. But, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. said, "in the real world, a prisoner who wants access to DNA evidence is interested in overturning his conviction."

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan said that Skinner was in something of a Catch-22, because he couldn't challenge the wrongfulness of his conviction without knowing the results of the DNA test.

The question that seems to hang over the arguments - but was never broached - was: Why not just perform the test?

Barry Scheck, co-director of the Innocence Project at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, said cases needlessly drag on when prosecutors resist such requests.

"I'm still stunned by the irrational decisions of some prosecutors and law enforcement not just to do the test and find out," he said. "It's much cheaper and faster just to do it than to litigate."

Switzer, the prosecutor, said the case has "ramifications for district attorneys all across the state, especially where the defendant waits so long before even filing a civil rights lawsuit."

Switzer has not discussed the case publicly, but in her statement, she said Texas procedure for obtaining evidence "is ample and reasonable, and Mr. Skinner has been given plenty of opportunity to show that additional testing could prove his innocence, but he could not show that."

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The story can be found at:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/02/13/AR2011021303579.html?sid=ST2011021400582

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PUBLISHER'S NOTE: The Toronto Star, my previous employer for more than twenty incredible years, has put considerable effort into exposing the harm caused by Dr. Charles Smith and his protectors - and into pushing for reform of Ontario's forensic pediatric pathology system. The Star has a "topic" section which focuses on recent stories related to Dr. Charles Smith. It can be accessed at:

http://www.thestar.com/topic/charlessmith

For a breakdown of some of the cases, issues and controversies this Blog is currently following, please turn to:

http://www.blogger.com/post-edit.g?blogID=120008354894645705&postID=8369513443994476774

Harold Levy: Publisher; The Charles Smith Blog; hlevy15@gmail.com;